PLACER COUNTY, Calif. Pastor Casey Tinnin leads a congregational church in the Sacramento suburb of Loomis. He is also gay. After one Sunday service this past January, a man named Kyle approached, looking for some advice. As Tinnin remembers the conversation, Kyle said that he and his wife Alley had a transgender teenager and were worried about what living in Loomis would be like. Tinnin understood the concern.

Loomis sits in Placer County , an island of political and cultural red in the sea of California blue. It has relatively few ethnic and racial minorities, at least by California standards, with a significant population of Mormons and an even larger number of evangelicals. In the western part of the county that includes Loomis and the other Sacramento suburbs, many attend a Pentecostal megachurch called Destiny that is led by an outspoken right-wing pastor who frequently attacks what he has called the LGBTQ, trans mafia.

But Placer County has been changing, thanks to an influx of young families drawn to its affordable homes and high-performing schools. Many of the newcomers are from the San Francisco Bay Area or other parts of California, and they have brought their more progressive values with them. Some ended up at the United Congregational Church of Loomis, which hired Tinnin seven years ago in no small part, church leaders made clear, because they wanted to make their congregation a welcoming place for LGBTQ+ worshippers. Meeting with prospective parishioners like Kyle and Alley was an important part of the pastors job.

Over dinner at a local restaurant, about a month after Kyle had first approached him, Tinnin talked about the programs he and the Loomis Church had created. He said he was especially proud of a secular LGBTQ+ youth support group called the Landing Spot. It offered monthly meetings through local libraries and the counseling offices in some of the public schools providing, Tinnin said, the kind of validation and mentorship that these kids frequently needed but didnt get. The presence of LGBTQ+ adults was important, he said, because it gave the teens positive role models and the chance to learn from people who had gone through similar experiences. In my mind, how communities thrive is through intergenerational relationships, he said.

Kyle and Alley seemed pleased to hear that, Tinnin says. But they also had questions, including some about confidentiality and how others in the community were reacting to the project. Parents dont want me talking encouraging this lifestyle, Tinnin conceded to Kyle and Alley. Were like this close to having parents freaking the fuck out, he added in his characteristically blunt way.

It helped that meetings were in school libraries or church buildings, Tinnin went on to explain. Kids would say theyre going to youth group, he told Kyle and Alley. Its not lying, but its not fully telling the truth ... It keeps them safe. Thats all I fucking care about.

The back-and-forth went on for about 90 minutes, as Tinnin remembers it, and sometimes the conversation got intense, with all three of them sharing deeply personal stories about their own difficult experiences with less tolerant congregations or communities. Its a very pastoral conversation where I am allowing them to be vulnerable and I am being vulnerable, in a way to support them and their families, Tinnin told me.

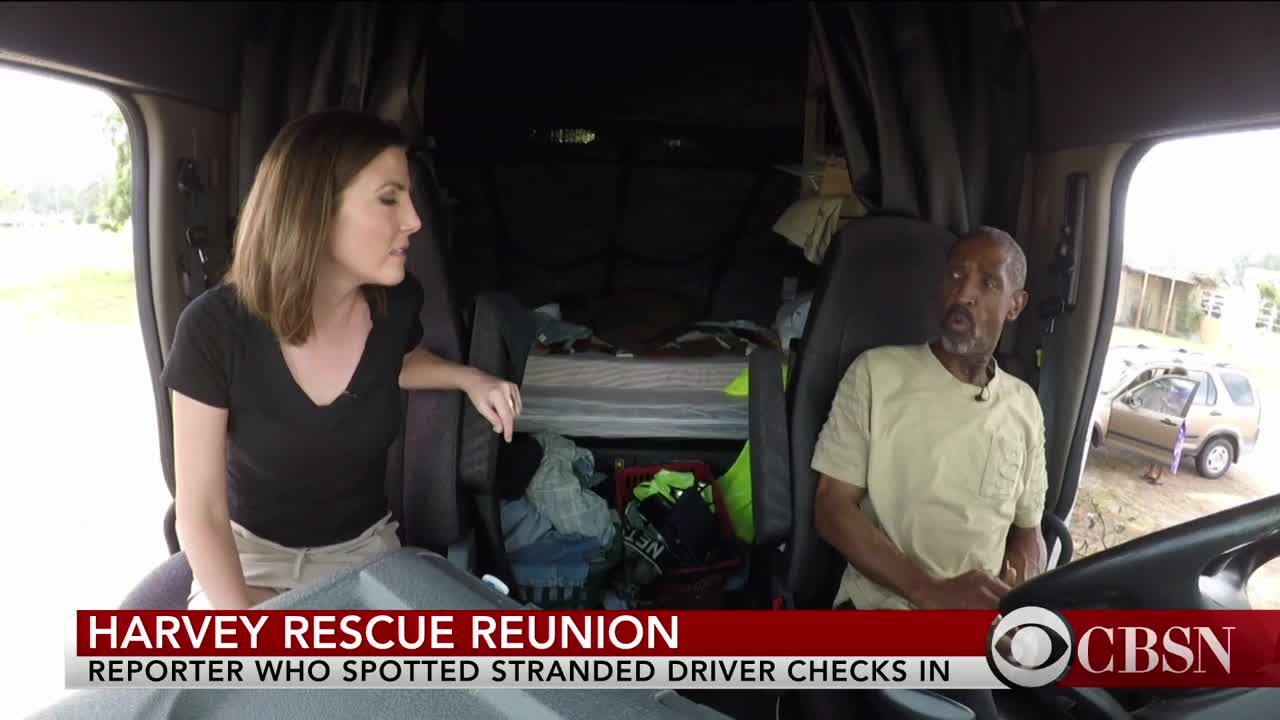

Tinnin says he felt good about the support hed offered Kyle and Alley and their teenager, though he also remembers thinking and telling his husband that there was something odd about the way the couple had steered the conversation. As it turns out, there was. A month and a half later, while Tinnin was at lunch with friends, his phone started buzzing with messages: The right-wing group Project Veritas had just posted a video with excerpts from the dinner, presenting it as an expos of how Tinnin discusses sexual identity and gender with young kids behind their parents backs.

Tinnin never figured out who Kyle and Alley really were, or what prompted Project Veritas to focus on him. But he and his allies couldnt dwell on those questions because they had a more important issue on their hands. The video had prompted an outcry, with parents and local conservatives calling on the areas school districts to sever ties with the Landing Spot. (Project Veritas didnt answer my questions about the videos origins or production, instead responding to my inquiry with two social media posts describing the footage and the angry response it generated, along with a link to the video itself.)

The debate over Tinnin, the Landing Spot and their respective roles in the community would play out over the following weeks and months not as an isolated controversy, but as part of a broader, escalating debate about children, schools and LGBTQ+ issues that is still ripping apart Placer County today. Clashes have erupted over curriculum issues, like whether elementary school lesson plans should highlight the role of prominent gay figures in history. More recent disputes have centered on issues related to gender identity, including parental rights proposals that would require teachers to notify parents when students request to use names or pronouns other than the ones on their school documents.

The fights in Placer County look a lot like the fights that have upended local and state politics everywhere from Virginia to Michigan to Colorado , and that have infiltrated the 2024 presidential campaign . But the debates in Placer County have been going on longer than in most places. They first burst into public view in 2019, when protests by conservative parents in the city of Rocklin made national headlines, and theyre rooted in political and cultural changes that started sweeping through California many years before that. That makes the story of Placer Countys conflicts a particularly useful case study for understanding who is fighting these battles and why, and whats really at stake.

Arguments about sexual orientation and gender identity have been a mainstay of American politics for roughly 50 years, with talk about the well-being of children, and different ideas of what that means, playing a prominent role. In the 1970s, just a few years after the Stonewall uprising in New York City launched the modern gay rights movement, former beauty queen Anita Bryant led a Save Our Children campaign to overturn a Miami ordinance that prohibited schools from firing teachers because of their sexuality. Her campaign succeeded and led to similar efforts around the country, while helping to inject the idea of grooming into the political dialogue. Homosexuals cannot reproduce, Bryant said , so they must recruit.

The current round of conflict playing out in America comes after what seemed like a detente of sorts, following the Supreme Courts legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015 and polls documenting a dramatic, unmistakable uptick in acceptance of gay, lesbian and bisexual Americans as citizens deserving of equal treatment. With more and more Americans identifying openly as part of the LGBTQ+ community, and the change especially pronounced among young people who speak as freely about exploring gender identity as they do about sexual orientation, some conservatives have pushed back on a variety of fronts advocating everything from boycotts of retailers that celebrate Pride month to restrictions and prohibitions on gender-affirming care.

One animating argument behind these efforts is the conservatives sense that they are under attack that they are having a radical ideology forced upon them in ways that undermine not just their values, but also their rights as parents to determine whats best for their children. That sentiment can be difficult to understand at a time when conservatives have so much power in so many parts of the country, and when they may be less than a year away from an election that gives them full control in Washington, D.C. It makes more sense in Placer County, where conservatives say they were minding their own business, raising their kids as they saw fit, until a coalition of Democratic state officials, teacher union leaders and LGBTQ+ activists started interfering.

But to the progressives in Placer County, its still the conservatives and traditionalists who wield the ultimate power through megachurches like Destiny and a political organization that one of Destinys leaders now operates, as well as through governing majorities on several local school boards. Conservatives in Placer County also have their own set of powerful, well-funded allies, including national advocacy organizations like Moms for Liberty and a California-based group called the Coalition for Parental Rights.

Progressives say the conservatives also fail to acknowledge why theres been such a strong push to affirm the LGBTQ+ community namely, that its a reaction to the historic exclusion of LGBTQ+ Americans from public life and public discussion, as well as the discrimination and outright abuse long directed toward members of the LGBTQ+ community.

This concern is especially acute for teenagers who are LGBTQ+, or who have questions about whether they might be. In Placer County, as in the rest of America, many say they still struggle that they cant always count on adults, not even their own parents, for support. Its why Placers teens have emerged as some of the most passionate defenders of the Landing Spot and most determined opponents of the new parental rights proposals, giving these philosophical and religious battles a distinctly generational bent.

Tinnin can identify with these LGBTQ+ teens, because he remembers what it was like to be one. We spoke in person for the first time this fall in Roseville, which is Placer Countys most populated city and the one closest to Sacramento. Like any proper youth pastor, Tinnin straddles the line between gently hip and gently aging: On the day we met, he was wearing a Stonewall T-shirt and gauged earrings about a centimeter wide. He has dark hair starting to show gray, a broad smile and thin, deep-set eyes behind thick-rimmed glasses.

We were at a local coffee shop a place he picked, he told me, because it has always been welcoming to LGBTQ+ customers. Since the Project Veritas video came out, Tinnin says he has been more careful about where he goes and who he sees. But he realizes that having any safe place to go represents an important change, both in the area and in his life.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)